Space and Time

Conversation 25, Socrates Worldview 19/22

SOCRATES. How are you today, Critobulus? You rode well.

CRITOBULUS. I took your warning to heart and tried not to think of quantum mechanics while I was riding. My head is still spinning from yesterday’s discussion.

S. I have worse in store for you. I kept one of the juiciest bits of quantum physics for today. Have you heard of the Delayed Choice Quantum Eraser?

C. No! It sounds like something that could suck the entire universe down a worm hole. Is it safe to even think about it?

S. Safe enough, although it might unsettle your confidence in your understanding of the world around you. Ah, here are Adeimantus and Euthydemus.

ADEIMANTUS. What have you in store for us today, Socrates?

S. Rather a mixed bag, beginning with non-locality.

C. It’s something to do with a Delayed Choice Quantum Eraser, whatever that may be.

S. Before I get to that, I will introduce you to the Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen paradox. Perhaps you are already familiar with it?

A. Perhaps you had better run through it, Socrates.

S. Well then, in the version described by Bohm, we consider particles with spin. Electrons are said to have spin one half, which means whenever I measure the spin of an electron, I can get only one of two possible results, spin ‘up’ or spin ‘down’. These are quantum-mechanical states. The wavefunction for an electron is a supposition, that is, a combination, of spin up and spin down. When I measure the spin of an electron, I choose an axis to measure along. The axis can be in any direction. The result of my measurement will be either ‘up’ along the axis, or ‘down’ along the axis. I can’t predict with certainty what the result of each measurement will be. The wavefunction only gives me the probability of up or down. Are you with me so far?

A. It seems clear enough, given what you have previously told us about quantum mechanics.

S. Now suppose I do an experiment in which energetic photons decay into a pairs of particles, one an electron and the other a positron. A positron is the antiparticle of an electron. It has a positive charge, and like an electron, it has a spin of one half. Now, a photon has a spin of zero, and spin is related to angular momentum. I’m sure you know that angular momentum is conserved in any physical process, so spin is also conserved. The spin of the photon before it decays is zero, so the total spin of the electron-positron pair after the decay is zero. This means that if the electron has spin up, then the positron must have spin down, and vice versa, so the total spin is zero. The spin states of the electron and positron are tied together and must be combined in one wavefunction. We say that the particles are ‘entangled’.

A. Will they always remain entangled?

S. Good question, Adeimantus. As the electron and positron go on their way, in opposite directions since the total linear momentum is conserved as well as the angular momentum, they might encounter other particles and become entangled with them also. Soon they are entangled with a vast number of other things. Their wavefunctions now depend on a large number of other variables and the dependence of the electron on the positron gets overpowered by all these other variables. Although it may still be there, it is no longer feasible to separate the influence of the positron state on the electron state from all the other influences. This is called ‘decoherence’.

C. What about non-locality?

S. Thank you, Critobulus. Let’s suppose our electron-positron pair is in empty space, away from influences that could cause decoherence. They move apart from where the decay of the photon occurred. Some time later the particles are thousands of kilometres apart. At a pre-arranged time, an observer measures the spin of the electron along a pre-arranged axis. The measured spin is either ‘up’ or ‘down’ along that axis. Another observer measures the spin of the positron at the same time using the same axis and the result is either ‘up’ or ‘down’. They repeat the experiment many times with other electron-positron pairs and record their results. Later, the two observers get together and compare their results. What do you think they find?

C. Nonlocality!

S. You are guessing, Critobulus. They both find that the spin is sometimes ‘up’ and sometimes ‘down’. This is not unexpected because they are the only results that quantum mechanics permits. Whether the result of a given measurement will be ‘up’ or ‘down’ cannot be predicted with certainty, since only the probability of ‘up’ or ‘down’ can be calculated from the wavefunction. But the surprising result is that the measured spins of the electron and positron are perfectly correlated. Whenever the spin of the electron is measured as ‘up’, the spin of its entangled positron is measured as ‘down’. This is comforting because it means that the total spin is always conserved, but how does the correlation happen even though neither spin measurement result can be predicted with certainty? Now we get to non-locality, Critobulus. The measurement on the electron and the positron can be made so far apart that a light signal does not have time to travel from one to the other to convey the result of one measurement to the other. In classical physics, no signal or influence can travel faster than light, but in our quantum experiment, a measurement in one place seems to know what the result of the measurement in a distant place was or will be. That is non-locality, and it is totally at odds with classical physics.

A. What would classical physics predict for this experiment?

S. In classical physics, each particle has a well-defined axis of spin, regardless of whether I measure it or not. Philosophically, we could say that the spin is an objective reality that exists all the time. The measured spin would depend on the angle between the axis of the particle’s spin and the axis of measurement. We would measure the maximum value when the spin axis and measurement axis were aligned and zero when the two axes were at right angles. At other angles, we would get a well-defined, intermediate value. The electron and positron spins would be created in opposite directions, so the total spin would be zero. The electron and positron would keep the same spin directions as they moved apart, so we would always observe them to have opposite spins. In classical physics, the spin axis of a particle is a local variable which determines the result of our measurement. We don’t need to know anything about the local variables of the positron to predict the result for the electron. But in quantum mechanics, we can only get ‘up’ or ’down’ for spin measurements and we can’t predict the result, only the probability, so how can the electron and positron spin measurements be correlated? This is the so-called paradox.

C. What is the explanation, Socrates?

S. There isn’t any explanation. The universe is non-local at the quantum scale, and that’s all there is to it. How does an electron going through the two-slit experiment know that both slits are there so it can interfere with itself, even though, perhaps, it only goes through one slit?

A. But is there any way to imagine this nonlocality?

S. Not with any precision. It’s as if the whole universe was encoded at each point of space. As I mentioned in an earlier discussion1, the universe is a bit like a hologram in which every section of the hologram encodes the entire image. If you try too hard to visualise it, you will fry your brain, which is why I advise against thinking about nonlocality when you are on your bike.

C. Hmmm.

S. It gets worse when we bring in time, Critobulus. Shall we now consider the Delayed Choice Quantum Eraser?

C. Let’s get it over with.

S. Very well. This time, instead of an entangled electron-positron pair, we have a pair of entangled photons. Photons have a property called polarisation. Whenever I measure the polarisation of a photon, it is either along the axis of my measuring device, which I call ‘vertical’, or at right angles to it, which I call ‘horizontal’. Both ‘vertical’ and ‘horizontal’ are at right angles to the direction the photon is moving in. So, polarization is a bit like the spin of an electron in that you can only get one of two possible results when you do a measurement, and you can’t predict which result you will get, only the probability. Are you with me?

C. Well enough so far. Is it something to do with sunglasses?

S. Well, yes Critobulus. Sunlight reflecting off a wet road gets horizontally polarized. Your polarizing sunglasses only let through vertically polarized photons, so the glare from reflected light is filtered out.

EUTHYDEMUS. So physics can be useful after all.

S. I’m glad you are still with us, Euthydemus. Now, I need to describe the experimental setup for the Delayed Choice Quantum Eraser. This is not just a thought experiment; the experiment has actually been done. See Ananthaswamy’s book (Ananthaswamy 2018, Ch. 5) if you want a more complete description. It will help if I draw a couple of pictures, which I base on those in Ananthaswamy’s book.

(As before, Socrates took a stubby pencil from the pocket of his riding jersey and drew pictures on two paper napkins.)

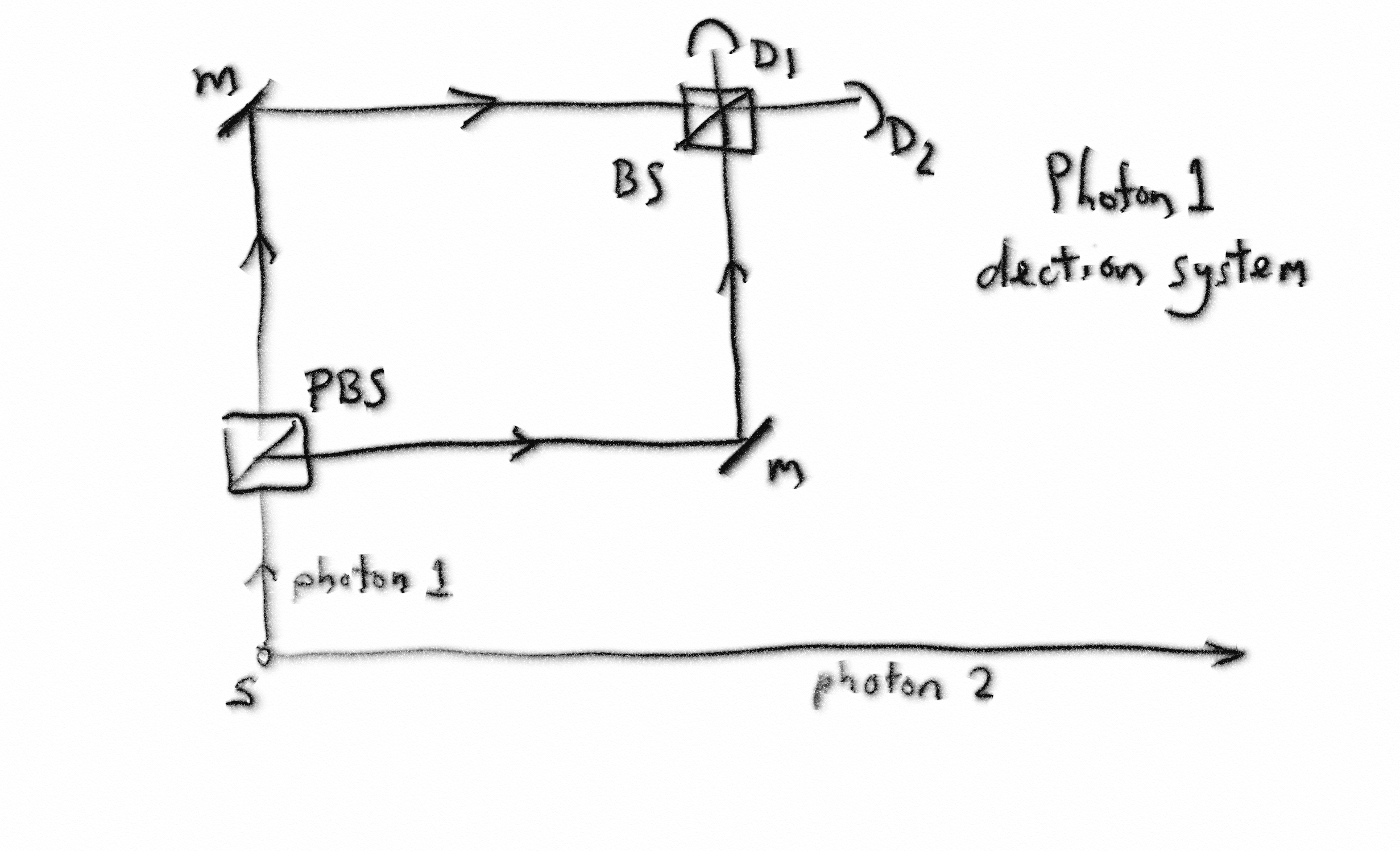

S. In this first picture, we have a source ‘S’ of entangled photons. In the source, atoms of a certain kind are ‘pumped’ with a laser into an excited state, and soon after they decay, emitting two photons. The photons are entangled in their polarization – if one is ‘vertical’, the other is ‘horizontal’. We direct one photon, let’s call it photon 1, into a nearby detection system. The other photon, photon 2, is allowed to go off towards a second detection system located very far away, over one hundred kilometres away in fact. The detection system for photon 1 is a variation on the Mach-Zehnder interferometer, but you only need to know that if you intend to look it up.

A. How does it work?

S. When photon 1 goes into the interferometer, it first encounters a beam splitter labelled ‘PBS’ in the picture. This causes some photons to go right and some to continue straight on. Let’s call the path to the right the ‘lower path’, and the path that goes straight on the ‘upper path’. We want to bring the paths back together, so we have the mirrors labelled ‘m’ to do that. For a start, let’s leave out the second beam splitter, the one labelled ‘BS’. What do you think we see at the detectors, D1 and D2?

A. The photons that took the lower path go into D1 and the photons that took the upper path go into D2.

S. Correct, Adeimantus. For each photon we only get one click, at either D1 or D2. The beam splitters send whole photons one way or the other. You can’t split individual photons. Without the second beam splitter, ‘BS’, the photons behave just like particles and seem to take either the upper or the lower path. There is no interference pattern.

C. Got it.

S. When we put the second beam splitter, ‘BS’, back in, what do you think happens?

C. We must get interference, or it wouldn’t be called an interferometer.

S. Your answer is right, Critobulus, but I would like to expand on the reasoning. With the beam splitter ‘BS’ in place, we have two ways for the photon to get to D1; it can go via the lower path and straight through BS, or it can go via the upper path and reflect off BS into D1. Similarly, there are two ways for the photon to get to D2; via the upper path and straight through BS, or via the lower path and reflected off BS. So, for each detector there are two alternative, indistinguishable, paths for the a photon to get there and we get interference.

A. What does the interference pattern look like in this case?

S. We can adjust the lengths of the lower and upper paths so that, for example, we get destructive interference between the two paths leading to D2, in which case we never see any photons in D2. The two paths going to D1 will then interfere constructively and all the photons will go into D1.

A. And in that case, there is no way of telling which way the photon went?

S. That’s right, Adeimantus, but this is where the experiment gets very clever. Firstly, the first beam splitter, the one labelled ‘PBS’, is of a special kind called a polarizing beam splitter. It sends, say, vertically polarized photons via the lower path, and horizontally polarised photons via the upper path.

A. But we still don’t know what the polarization of each photon was, and hence which path it took, unless we measure the polarisation. Won’t that disrupt the interference pattern?

S. It would, but there is a way to measure the polarization without doing anything to photon 1. We use photon 2. Remember, photon 1 and photon 2 are entangled so that if the polarization of photon 1 is vertical, photon 2 must be horizontal and vice versa. So, in the experiment we measure the polarization of photon 2 and that tells us what the polarization of photon 1 was, and then we know which path photon 1 took through the Mach-Zehnder interferometer. The second, entangled photon carries ‘which-way’ information about the path of photon 1. What will we see at D1 and D2 now?

A. Since we have a way of knowing which path photon 1 took, it should behave like a particle and we should not see interference, so we should get some detections at D1 and some at D2.

S. Right again, Adeimantus. But now we get even cleverer, if that is possible. Suppose when photon 2 gets to its detection system, we scramble its polarization before we measure it. Now we have erased the which-way information for photon 1. That’s why it’s called the quantum eraser, Critobulus. Will we get back the interference pattern for photon 1?

C. I honestly don’t know, Socrates. What about the ‘delayed choice’ bit?

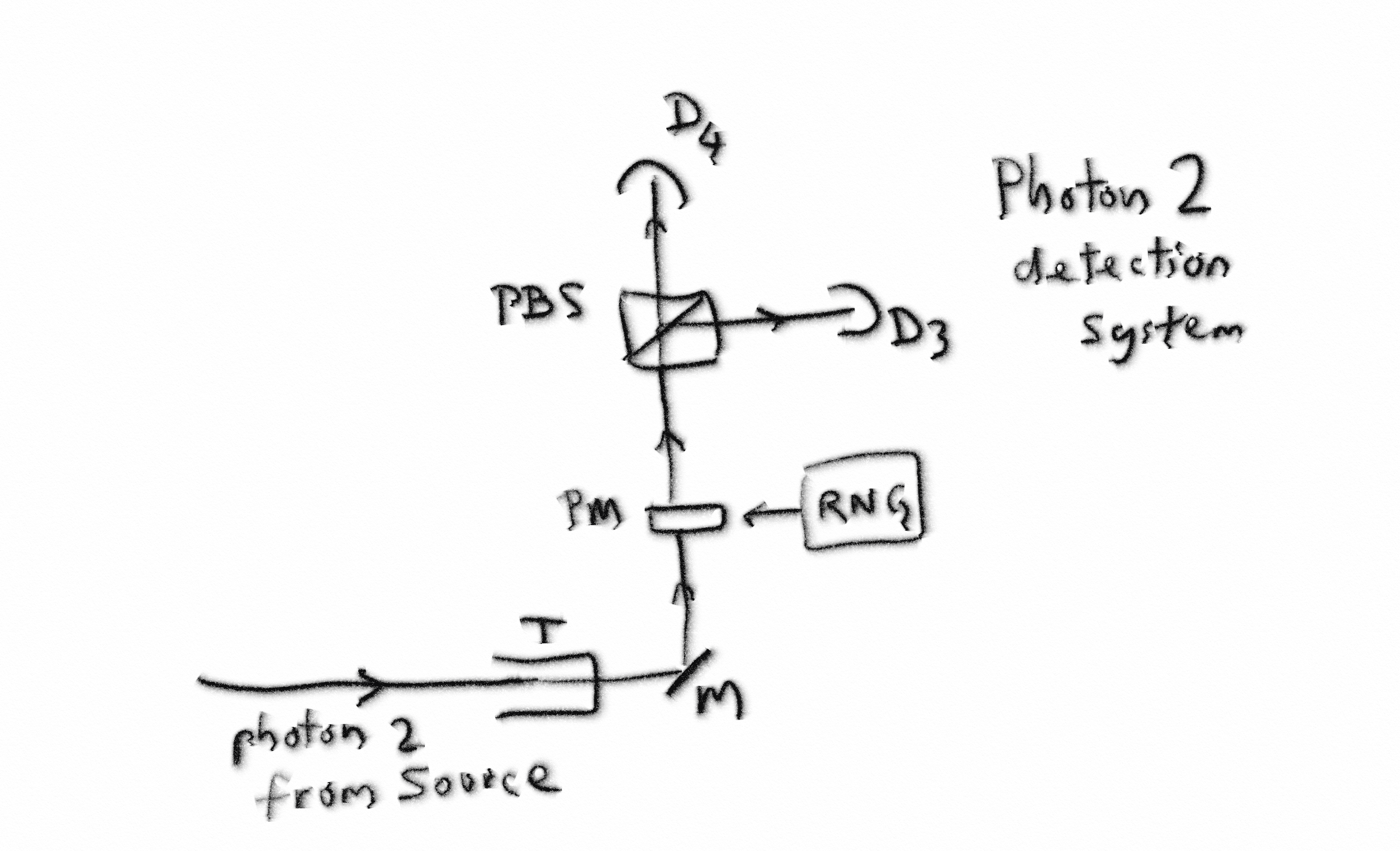

S. Let’s take a closer look at our detection system for photon 2, which I have drawn on the second napkin. We collect photon 2 with a powerful telescope ‘T’ and bounce it into the detector system via mirror ‘m’. At this point, we have a choice to make. We have a device called a polarization modulator in the path pf photon 2. It’s labelled ‘pm’ in my picture. We can choose to tell the polarization modulator to let photon 2 go through unchanged, in which case it still carries the which-way information for photon 1. Alternatively, we can choose to allow the polarization modulator to scramble the polarization of photon 2, and this erases the which-way information for photon 1. This is the ‘choice’ referred to in the name of the experiment.

C. And why do you say it is a delayed choice?

S. The distance between the detection systems for photon 1 and photon 2 is so great that by the time the choice for photon 2 is made, photon 1 has been detected and recorded in macroscopic systems. The detection of photon 1 is done and dusted before photon 2 gets to its detector. That’s why we say the choice of whether or not to erase the which-way information carried by photon 2 is delayed. If the distance between the detection systems was great enough, say if the photon 2 detection was on another star, I could have collected a whole lot of photon 1 results and published them in a hardcopy journal before the decision to erase, or not, the which-way polarisation information for any of the photon 2’s was ever made.

A. So, do we see an interference pattern if the which-way information of photon 2 is erased?

S. We do, Adeimantus! If the photon 1 and the photon 2 observers get together and compare their measurements, they find that the detections in the photon 1 system that correspond to photon 2 having its ‘which-way’ information erased show an interference pattern, while those photon 1 detections for which photon 2 retained its ‘which-way’ information showed no interference pattern.

C. Isn’t that what we expected?

S. Yes, Critobulus, but you need to think about it more to appreciate how truly strange and remarkable the result is. Let’s look more closely about the choice to erase, or not. In our detection system for photon 2 we have a device called a random number generator. It is labelled ‘RNG’ in the picture. This device is a quantum system that generates a number on demand. The number can be either 0 or 1, but there is no way of predicting what the number will be. I set up my experiment so that if the random number generator gives a 0, the polarization modulator allows photon 2 to go through with no change to its polarization. The ‘which-way’ information for the entangled photon 1 is not erased. If the random number generator produces a 1, then the polarization modulator scrambles the polarization of photon 2 and erases the ‘which-way’ information for photon 1.

A. So when photon 1 is detected, there is no way of predicting whether or not the which-way information carried by photon 2 is going to be erased?

S. Correct. Suppose as soon as I detect photon 1, I send a signal to the photon 2 detection system to tell it whether photon 1 went into detector D1 or D2. Firstly, a detection at D1 doesn’t tell me whether photon 1 suffered interference or not. Secondly, a physical signal can’t travel faster than light, so it can’t catch up to photon 2 and influence the random number generator in time to affect its output for photon 2. The random number generator appears to ‘know’ whether photon 1 is part of an interference pattern, or not, before photon 2 gets to its detector.

A. That is remarkable.

S. I have spent a lot of time describing this experiment in detail so you can all appreciate how truly remarkable it is. Information about what happens at the photon 2 detection systems seems to be already encoded at the location of the photon 1 detection system and vice versa. This is nonlocality. Furthermore, what happens to photon 1 seems to influence what happens to photon 2 in the future faster than light, or looking at it the other way, what happens to photon 2 seems to influence what happened to photon 1 in the past. It is as if information about all times, future and past, is present everywhere and at all times. It is like time does not flow at the quantum level.

A. It seems that everything is predetermined at the quantum level. Does this extend to the everyday level? Is the flow of time just an illusion for us?

C. If I fall off my bike, it will still be your fault, Socrates.

S. No Critobulus, if you don’t heed my warning, it will be your fault if you fall off your bike. I think that answers your question, Adeimantus, but it is a question that demands a better answer, and I will come back to it. For now, I just want to emphasise that at the quantum level, space and time are not as we imagine them, if they exist at all.

E. How can space and time not exist?

S. The Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics says that it is meaningless to asks questions about the reality of what goes on between measurements. For a physicist, essential attributes of reality are the position and momentum of a thing, or its position at different times, its trajectory if you like. The Copenhagen interpretation says that those attributes of reality only gain definite values when we do a measurement. Some people go so far as to say that the thing does not exist between measurements, that it is the measurement that creates reality. I think that’s an unwarranted excursion into metaphysics and has no practical value. I prefer to think that an objective reality exists all the time, it’s just that our everyday notions of space and time do not apply to reality at the quantum scale. Our notions of space and time are conditioned by our macroscopic nature.

A. Don’t we already know from relativity that space and time are not as we commonly think?

S. True, Adeimantus, although not in precisely the same way. Special and General Relativity are classical theories in the sense that position and momentum can be measured simultaneously with arbitrary precision, unlike quantum mechanics. But it is true that space and time are tied together in Relativity. Special Relativity says that events that are simultaneous for one observer may not be simultaneous for an observer moving relative to the first. The difference becomes greater as the relative speed of the observers increases. When the relative speed is close to the speed of light, the distortion of space and time becomes so great that nothing can ever be observed moving faster than the speed of light.

A. What about General Relativity?

S. As I’m sure you know, General Relativity says that matter and energy distort spacetime and it is the distortion that produces gravity. Both Special and General Relativity have been extensively tested by experiments and no departures from their predictions have ever been verified. Physicist have become so used to the ideas of Relativity that they tend to forget how truly weird and contrary to everyday intuition are the relationships between space and time they imply. Do you know, physics doesn’t even tell us what causes inertia.

C. What do you mean by inertia?

S. Perhaps you have heard of Newton’s Law of Inertia, Critobulus? It says that an object remains at rest or continues to move with constant velocity unless a force acts on it. When you do exert a force on an object, it tends to resist being moved. That resistance is called inertia. The mass of an object is a measure of its inertia. The more massive an object, the harder you have to push it to get it to move with a certain acceleration. You know this from everyday experience. It is harder to throw a cannon ball than to throw a small stone.

C. I’ve never tried to throw a cannon ball, but I will take your word for it.

S. Strictly speaking, the Law of Inertia applies only in what are called inertial frames of reference. These are coordinate systems, if you like, that are at rest or moving with constant velocity relative to a frame that is at rest. If you are in a vehicle that is an inertial frame of reference and you can’t look out of the window, there is no experiment you can do that can show whether you are moving, or not.

A. Are there frames of reference that are not inertial?

S. Indeed there are, Adeimantus. If I am in a rocket ship that is rotating rapidly, I can easily do an experiment that shows I am rotating. If I put a cup of coffee down on a table in my rotating rocket ship, it might fly off towards the outside of the ship, and even if it doesn’t, the coffee will tend to rise on the side of the cup that is towards the outside of the ship. It looks like forces are acting on the cup and the coffee. Similarly, if my rocket ship is moving in a straight line and suddenly begins to decelerate, I am likely to be thrown forward out of my seat. Again, it looks like a force is acting on me. The appearance of these ‘fictitious’ forces tells me that my frame of reference is rotating or accelerating. It is not an inertial frame of reference.

A. When you say that an inertial frame is at rest or moving, relative to what is it at rest or moving. My frame of reference might be at rest relative to the ground and you say it is inertial, but it is accelerating relative to an accelerating car, so it is not inertial.

S. You have hit the nail on the head, Adeimantus. Historically, physicists say ‘at rest relative to the fixed stars’. This is not a precise idea. It might be better to say, ‘at rest relative to the average of the mass in the universe’, but this is also problematic. We have now come to a concept that Einstein dubbed ‘Mach’s Principle’ after Ernst Mach who articulated something like it. The general Idea is that mass comes from some kind of interaction with everything in the universe.

E. The same Mach as Mach-Zehnder?

S. Well spotted, Euthydemus. The Mach of Mack-Zehnder was Ernst Mach’s son Ludwig. Einstein hoped to derive Mach’s Principle from General Relativity but did not succeed. Physicists have made various attempts to discover the physical source of inertia, or of mass, but so far there is no consensus about where mass comes from. The most popular theory, I suppose, is that inertia is a by-product of gravity. Some have suggested it is a quantum effect. I refer you to a paper by Woodward and Mahood (Woodward and Mahood 1999) if you want to read more about it, although I warn you it is rather technical.

A. What is your opinion about the source of inertia?

S. My instinct is that inertia is something to do with space and time at the quantum level. As I’ve said, at the quantum scale, everywhere and every time is present at each place and time, so in a sense Mach could be right: it is the influence of the whole universe, past present and future, on an object that gives it its mass and is responsible for inertia. But that’s just an instinct. I doubt if the exact workings of it can ever be discovered.

A. Forever hidden below the fundamental limits of science.

S. I expect so, Adeimantus, and there are other problems with physics. Quantum field theory does a good job of explaining electromagnetism, as well as the strong and weak nuclear forces. There is a problem that the energy of the vacuum works out to be infinite in these theories, which can’t be right, but the energy differences between states work out correctly. It’s mostly right, but not quite right. Another problem is that there is no accepted quantum theory of gravity. In fact, quantum mechanics and General Relativity have fundamental incompatibilities.

A. In what way are they incompatible, Socrates?

S. As I said a minute ago, General Relativity is a classical theory: the position of an object can vary smoothly and be measured with arbitrary position. Now, General Relativity predicts situations where mathematical singularities can arise. For example, at the centre of a black hole, a physical quantity might vary as one divided by x, where x measures the position of something. As x tends towards zero, one divided by x tends towards infinity. This is what is meant by a singularity. A physical quantity tending to infinity is a sign that something is not quite right with the theory. In quantum mechanics, the uncertainty principle prevents us from saying the position of a thing is precisely zero, because that would imply there was no uncertainty in its position, which is not allowed. Quantum theory seems to suggest that spacetime might come in lumps at a very small scale, and that would avoid the problem of singularities because a position variable like x could never be precisely zero, but unfortunately space and time are not variables that can be quantised in the formalism of quantum mechanics. If you quantise the electromagnetic field, you find the lumps, or quanta, are photons. Quantising the weak nuclear field gives you W bosons, and quantising the strong nuclear field gives you gluons, the particles that hold quarks together. But quantising gravity doesn’t work so well. The electromagnetic, weak, and strong fields all vary with space and time, but gravity is nothing but the curvature of spacetime itself. The underlying problem in all of this seems to be our notions of space and time.

A. And unfortunately the mystery is beyond our reach?

S. It seems so, Adeimantus, although some work in physics does give us tantalising glimpses of the way things might be. Some clever physicists have shown that a certain type of two-dimensional quantum field is mathematically equivalent to a three-dimensional space that is a cosmological solution of the equations of General Relativity (Becker 2022). The quantum field is like a hologram, as I have mentioned before (Musser 2022). Every part of our universe is mapped to any small part of the quantum space. The amazing thing is that distance in the three-dimensional space is related to entanglement in the quantum space. Things that are highly entangled in the quantum space are close to each other in our space-time universe. I find this mind-boggling.

C. So do I!

S. I said I would come back to time and predetermination. The question was, if information about all times is present everywhere and at all times, it is like time does not flow at the quantum level, so how does it seem that time flows in everyday life?

C. Yes that was the question. How does time seem to flow?

S. Firstly let us talk about classical statistical mechanics. Suppose we have some gas in a jar. The gas is composed of a vast number of identical molecules jiggling around. Suppose further that I have contrived to get all the gas into one half of the jar, and it is kept in that half by a partition across the jar. Now, at a certain moment I pull out the partition. What happens?

A. The gas spreads to occupy the half of the jar that was formerly empty.

S. Correct. Now what has this to do with the flow of time?

C. Please tell us, Socrates.

S. Suppose I have a video of people walking down a street and I play it backwards. Does it look strange? Can I tell that it’s running backwards?

C. Of course.

S. Now suppose I have a video of the collision of two billiard balls. There is nothing in the background except the green baize of the table. Can I tell if this video is running backwards?

C. Since we are doing a lot of supposing, I will suppose that we can’t tell.

S. You suppose correctly, Critobulus. Why can I tell that the video of the people walking is playing backwards, but not the video of the billiard balls?

A. It’s my turn to suppose. I suppose it is because the equations of motion for a simple event like the collision of billiard balls are valid if time is reversed, so the backwards video of a collision is a valid collision that obeys the laws of physics. On the other hand, a large number of people walking backwards is improbable and looks strange.

C. Unless they are attempting to break some record in the Guinness Book of Records.

S. Even then it would look unusual, but if I examined each person in my backwards video of walking people, I would not find that they were breaking any law of physics. It is merely that a whole lot of people walking backwards is unusual, and therefore, improbable in my experience. What about my jar of gas? If I play a video of it backwards, will I be able to tell that the video is playing backwards?

E. Yes. Even I could spot that, Socrates.

S. When I pull out the partition in the jar, the molecules continue to jiggle as before, but those that happen to jiggle towards where the partition used to be keep going. They move into the empty half of the jar. If I were able to examine every collision between the gas molecules, I would find that, like the collision of the billiard balls, the collisions look equally valid if time is reversed. So, it is nothing to do with the collisions themselves that tells me that the video is running backwards, it is the probability that all the molecules will suddenly and spontaneously move into one half of the jar. It is the improbability of certain collective motions ever being reversed that gives direction to time, that seems to make it flow. This has been called ‘the arrow of time’.

A. Is this something to do with entropy?

S. It certainly is, Adeimantus. Entropy is a measure of randomness. In the case of the jar of gas when the partition is removed, it is vastly more likely that the molecules will adopt the more random configuration of occupying the whole jar than the more ordered configuration of being in only half of the jar. The entropy for the configuration with the gas in the whole jar is greater than the entropy for the configuration with the gas in half of the jar. This is an example of the Second Law of Thermodynamics, which says that the entropy of an isolated system always increases until it reaches a maximum.

A. Why did you say the system has to be isolated.

S. This is the physicists’ way of saying that I have not laid my hands on the system, metaphorically, to do work on it by exerting energy. If I do work on the system, I can get its entropy to decrease, but it is not isolated because I am doing things to it. Take the gas in the jar: if the jar has a piston at one end, I can push the piston into the jar and force the gas back into one half. It takes energy to do this because the pressure of the gas resists my push. Consider a refrigerator. I supply energy to it in the form of electricity and pump heat out of it. Water in the refrigerator cools down and freezes into ice. The water molecules in the ice are more ordered than when it was a liquid. The entropy of the water decreases when it turns into ice, but I had to expend energy to get that to happen. Now consider a living organism. It collects hydrogen, carbon, and oxygen from the environment to build its body. In the body, these chemicals are more ordered that when they were floating around in the environment. Their entropy has decreased, and energy had to be expended to do it.

C. Where did the energy come from?

E. God supplied it.

S. Ultimately perhaps, Euthydemus, but let’s look at the mechanism, which we know. For life on earth, the energy needed to organise living bodies comes from the sun. It is captured in plants through the process of photosynthesis and passes to animals when they eat plants. There are other mechanism, but that’s the main one.

A. So, you are saying the flow of time for a living being, the appearance of past, present, and future, comes from the randomness of the vast number of parts that make them up?

S. Yes, that’s a way of putting it, Adeimantus. Simple physical processes involving few parts are reversible, but when very large numbers of parts work together, a process involving those many parts may be practically irreversible, even though it might be reversible in principle, because it is simply vastly improbable that the process should run backwards.

A. And this is not a quantum thing?

S. I have been talking from a classical physics viewpoint. Take the jar of gas again. In principle, each of the collisions of the molecules could run in reverse and the gas finish up back in the half of the jar where it started, but the slightest disturbance, even a photon of light bouncing off one of the molecules, could introduce a perturbation in the path of one of the molecules which would rapidly spread and amplify. It would be practically impossible to reverse the motion of the gas back to its starting configuration.

C. But you said you could do it with a piston.

S. So I did, but I am talking about the expansion of the gas running in reverse without being forced by the piston, so it would look like the video of the expansion running in reverse. It is so utterly improbable as to be impossible in practise, even under classical physics. For a quantum system, I think it may be impossible to reverse an observation even in principle.

A. Why do you say that, Socrates?

S. The Schrodinger equation of quantum mechanics is reversible in time, but it only gives us the probabilities of the outcomes of measurements, it does not predict the result of a measurement. If we prepare a system in a certain quantum state, let it evolve and perform a measurement on it, then repeat the experiment many times, we can get a different result each time. If there is some inaccessible underlying reality, which I have called my little fidget wheels, this suggests that the starting states are not truly the same but differ somehow (in a nonlocal way) in the settings of the fidget wheels. But we can’t see the fidget wheels, so we don’t know how they differ. If we try to reverse a measurement, we might get back the same quantum starting state, but we can’t know if the fidget wheel settings have been reversed to their original settings.

A. What if there is no underlying reality, no fidget wheels?

S. Then the universe really is random at the quantum scale and the argument against reversibility is harder to make. I think the honest answer is that nobody knows.

C. But is reversibility the same as predetermination?

S. I think that is the best question you have ever asked, Critobulus! Sadly, I can’t answer it either. I might think that if the past and future are fixed for all time, which we are calling predetermined, then you could look at it forwards and backwards and it would look valid. But what does it mean to look at it forwards and backwards? How can we talk about change in something that is unchanging. It is exceedingly difficult, if not impossible, for us to shake off our subjective notion of time. In any case, I should have said that the quantum experiments we have been discussing tell us that things at the quantum scale are correlated in ways that seems to defy our macroscopic notion of time, but that does not necessarily mean they are predetermined for all time, if it makes any sense to say such a thing.

C. Well then, does predetermination imply predictability?

S. You are on fire today, Critobulus! That question I can answer. Predetermination does not imply predictability. Whether the quantum world is predetermined or not, we know that we cannot predict the results of quantum measurements, only the probabilities of results.

A. What do you make of all of this, Euthydemus?

E. I think that Socrates has given God plenty of room to move in the quantum world, not that he needed Socrates to tell him that.

A. Socrates, do you agree with Euthydemus? Isn’t that what you have been leading up to all along? Couldn’t I argue that if you have a mapping from some sort of quantum space onto a space like the one we live in, doesn’t that imply that in some way the same things are going on in both spaces? Doesn’t that mean if you can’t observe God in our space, you won’t find him in the mapped space?

S. You fellows are making me earn my coffee this morning! I confess I have no answer, except to say that there still seems enough mystery to allow for some sort of mind to be behind the universe and be aware of what is going on and maybe control it.

A. But if consciousness emerges from macroscopic material brains, as you have said previously, can consciousness also emerge from your quantum-scale fidget wheels? Is it the same type of consciousness, or are they only analogous? If the same, can they interact?

S. We can speculate about such things, but we can’t possibly say one way or the other. I was once at a lecture by my professor of theoretical physics when he opined that there couldn’t be an omniscient God because his mind would have to have at least as many moving parts as the universe as a whole, and he didn’t think that was possible. That lecture was in the days before the quantum experiments I have been describing were done. But I think that what we have been talking about shows that there is plenty of room for the moving parts of a mind at the quantum scale. Of course, the God who inhabits the quantum world and influences the macroscopic world is probably not the ‘big man’ that the early bible pictures. We have that image because our antennae are tuned to pick up those traits, and it is the lens of our earthly experience that we see through. Naturally, we see the traits of a person, a conceptual person. But even the bible allows that God’s ‘home is in inaccessible light’ (The New Jerusalem Bible 1985, 1 Timothy 6:16) and that his thoughts are as high above our thoughts as the heavens are above the earth (The New Jerusalem Bible 1985, Isaiah 55:9).

A. But Socrates, after all your fine thoughts and words, do you not look up at the vastness of the night sky and think, if there is a God, why would he bother with mankind in this one, tiny corner of the universe?

S. Yes Adeimantus, that feeling has often assailed me. But I have come to understand, and it is science that gives this insight, that the vastness of the universe is at the same time real and also an illusion. Quantum mechanics, tested by experiment, tells us that things that are very far apart are connected, beneath the level of macroscopic things, in ways that unite them as if they were at the same place. We will talk about this another day. Although we can never delve below the macroscopic level to examine what is going on there, knowledge of this connectedness lessens my anxiety about the vastness of the universe and our apparently special place in it.

C. I still have trouble imagining how things going on at the quantum scale could affect us in the macroscopic world.

S. Let me go back to the analogy I’ve used before. Think of the quantum world as the fabric everything is made of and the things in the macroscopic world as garments made of the fabric. We know everything about the garments, but there are things we can never know about the fabric. Does that mean the fabric does not affect our garments?

C. I know I would rather have a shirt made of cotton than one made of polyester.

S. Me too! If the fabric deteriorates, my shirt is going to look a bit shabby. For most of our experience, goings on at the quantum scale do not affect the predictability of events at our scale, but there are situations in which quantum events can directly affect macroscopic events. Usually, we have to contrive such situations in a laboratory to shield the events of interest from stray macroscopic influences. But it seems to me conceivable that a powerful intelligence could manipulate macroscopic events through a host of unseen quantum events.

E. You mean God could do it?

S. Yes, Euthydeumus, something we call God.

C. Is that it for today, Socrates?

S. Yes, today’s ordeal is over. Well done all of you for staying with me. It was a difficult but, I felt, important point. We are nearing the end of my exposition of what I have called my worldview. Tomorrow, if you allow, I will draw together a few thoughts about the limits of science, and then I will summarise all we have discussed …. What is it, Critobulus? I can see that you’re bursting to say something.

C. I looked up that poem you quoted yesterday, Five Bells by Kenneth Slessor. You should have gone on one more line: ‘Time that is moved by little fidget wheels is not my time, THE FLOOD THAT DOES NOT FLOW’. Your Kenneth Slessor must have been a closet quantum physicist.

S. Kenneth Slessor would be astounded, and I hope pleased, that a bunch of bike-riding pseudo philosophers and would-be quantum physicists should find such inspiration in his poem. I wonder if it was predetermined that we should.

References

Ananthaswamy, Anil. 2018. Through two doors at once: the elegant experiment that captures the enigma of our quantum reality. New York: Dutton.

Becker, Adam. 2022. "The Origins of Space and Time." Scientific American (Scientific American) (February 2022): 22-29.

Musser, George. 2022. "Black Hole Mysteries Solved - Paradox Resolved." Scientific American 29-31.

1985. The New Jerusalem Bible. London: Darton, Longman, & Todd.

Woodward, James, and Thomas Mahood. 1999. "What is the Cause of Inertia?" Foundations of Physics 899-930.

1. See the conversation Defence of Christianity.